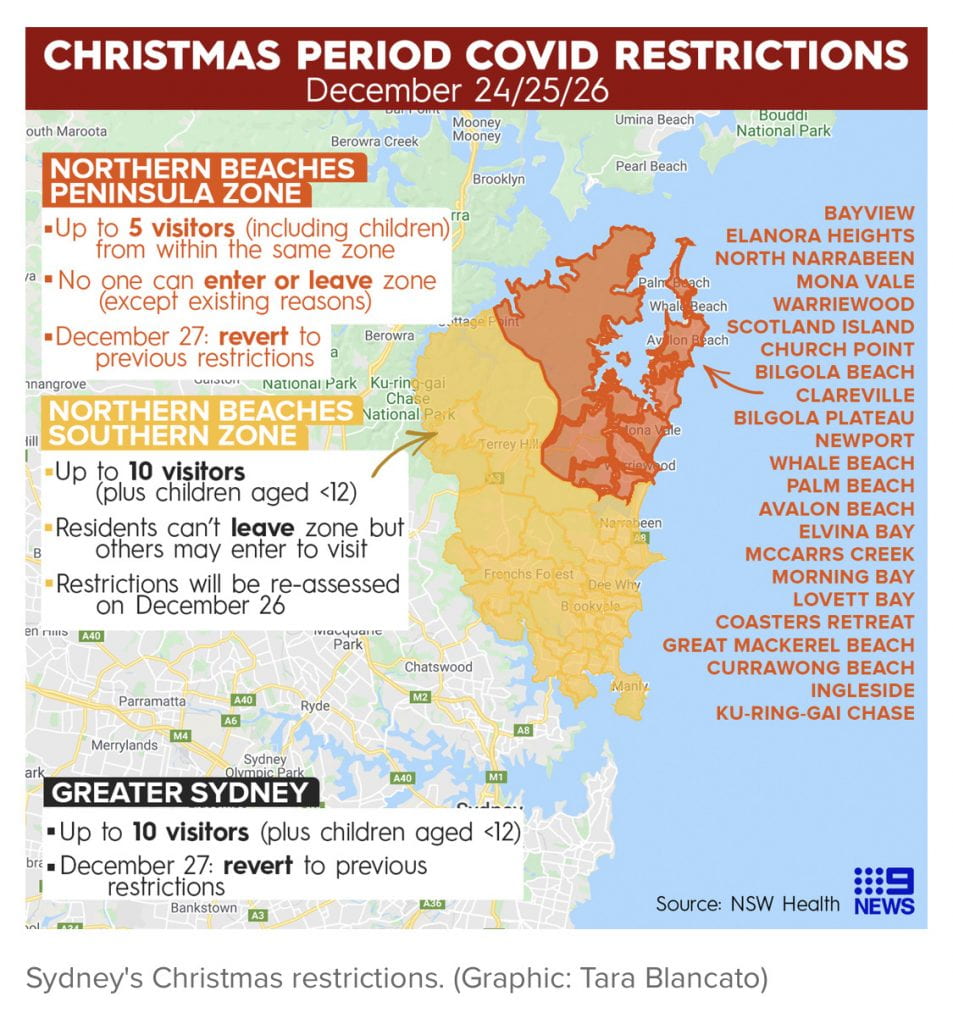

Things are getting under control in Australia. The Victorian lockdown is over. SA had a blip, but the pizza guy ended up having lied so it only lasted a few days. Looks like all the borders may finally be down in Oz by Dec although WA may be requiring some quarantine. NSW and VIC have had bugger all locally transmitted cases, but we are still getting lots of cases in hotel quarantine of returned travellers. That’s because overseas is a real mess still. Heaps of cases still in Europe and USA. A vaccine is looking promising, maybe in the first half of next year. Qantas is saying they will require people to have a vaccine to get on an international flight. Fair enough, I don’t want the anti-vaxxers on the plane with me anyway. Much less people wearing masks, less social distancing although businesses are supposed to be enforcing it. Some restaurants are more thorough than others. One more month to go in this year.

AUSTRALIA

GLOBAL

USA

ENGLAND

This article from the washington post is a good summary:

This article from the washington post is a good summary:

Australia has almost eliminated the coronavirus — by putting faith in science

November 5, 2020 at 8:16 p.m. GMT+11

SYDNEY — The Sydney Opera House has reopened. Almost 40,000 spectators attended the city’s rugby league grand final. Workers are being urged to return to their offices.

Australia has become a pandemic success story.

The nation of 26 million is close to eliminating community transmission of the coronavirus, having defeated a second wave just as infections surge again in Europe and the United States.

No new cases were reported on the island continent Thursday, and only seven since Saturday, besides travelers in hotel quarantine. Eighteen patients are hospitalized with covid-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. One is in an intensive care unit. Melbourne, the main hotbed of Australia’s outbreak that recently emerged from lockdown, has not reported a case since Oct. 30.

Meanwhile, in the United States, 52,049 people are hospitalized and 10,445 are in an ICU, according to the Covid Tracking Project, a volunteer effort to document the pandemic. America’s daily new cases topped 100,000 on Wednesday, and its death toll exceeds 234,000, a staggering figure even accounting for its greater population than Australia, which has recorded 907 deaths.

“I never thought we would really get to zero, which is amazing,” said Sharon Lewin, the Melbourne-based director of the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity, which provided forecasts in February that formed the basis of the Australian government’s response. “I’ve been going out nonstop, booking restaurants, shopping, getting my nails done and my hair cut.”

Australia’s coronavirus ‘dictator’ enforces a drastic lockdown. He’s still popular.

As North America, Europe, India, Brazil and other regions and countries struggle to bring tens of thousands of daily infections under control, Australia provides a real-time road map for democracies to manage the pandemic. Its experience, along with New Zealand’s, also shows that success in containing the virus isn’t limited to East Asian states (Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan) or those with authoritarian leaders (China, Vietnam).

Several practical measures contributed to Australia’s success, experts say. The country chose to quickly and tightly seal its borders, a step some others, notably in Europe, did not take. Health officials rapidly built up the manpower to track down and isolate outbreaks. And unlike the U.S. approach, all of Australia’s states either shut their domestic borders or severely limited movement for interstate and, in some cases, intrastate travelers.

Perhaps most important, though, leaders from across the ideological spectrum persuaded Australians to take the pandemic seriously early on and prepared them to give up civil liberties they had never lost before, even during two world wars.

“We told the public: ‘This is serious; we want your cooperation,’ ” said Marylouise McLaws, a Sydney-based epidemiologist at the University of New South Wales and a World Health Organization adviser.

A lack of partisan rancor increased the effectiveness of the message, McLaws said in an interview.

The conservative prime minister, Scott Morrison, formed a national cabinet with state leaders — known as premiers — from all parties to coordinate decisions. Political conflict was largely suspended, at least initially, and many Australians saw their politicians working together to avert a health crisis.

“Regardless of who you vote for, most Australians would agree their leaders have a real care for their constituents and a following of science,” McLaws said. “I think that helped dramatically.”

Heeding expert advice

Australians’ willingness to conform — especially in Melbourne, where residents endured a lengthy state-ordered lockdown — reflects political attitudes that differ from those in parts of the United States. In a nation where compulsory voting produces conventionally center-left or center-right political leaders, governments tend to be regarded as the solution to society’s problems rather than the cause.

Australia’s national response was led by Health Minister Greg Hunt, a former McKinsey & Co. management consultant and a Yale University graduate. Hunt and Morrison worked with the state premiers, who hold responsibility for on-the-ground health policy, to develop a common approach to the pandemic.

The government closed Australia’s borders to travelers from China on Feb. 1, the same day as the Trump administration in the United States. But unlike the Trump administration, which has criticized its primary infectious-disease adviser, Anthony S. Fauci, Hunt relied heavily on health experts from the start.

“In January and February, we were focused on containing the risk of a catastrophic outbreak,” Hunt said in an interview. “We had a clear strategic plan, which was the combination of containment and capacity-building.”

The secret to Australia’s success in beating the coronavirus? Being an island helps.

“We closed the border and concentrated on testing, tracing and social distancing,” he added. “We built up our capacity to fight the virus in primary and aged care and hospitals. We invested in ventilators, and vaccine and treatment research.”

Hunt’s department oversaw the purchase of huge amounts of protective equipment and clothing, including masks, which became mandatory on Aug. 2 in the state of Victoria, where Melbourne is located.

After a sick doctor in his 70s treated more than 70 people in the city before being diagnosed, Hunt accelerated a 10-year plan to phase in video consultations with physicians. Within 10 days, almost anyone in Australia could see a doctor over the Internet under Australia’s highly subsidized health-care system, including psychiatrists.

Australia plans free vaccines if trial succeeds

When private hospitals said they were in danger of going broke because non-urgent surgery had been canceled, the government stepped in with emergency funding, securing beds that could be used for coronavirus patients.

In private, Hunt swapped practical stories with his wife, Paula Hunt, a former infectious-

diseases nurse who kept a 1995 bestseller by U.S. science journalist Laurie Garrett, “The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance,” on her bedside table, he said.

AD

“It’s valuable to have a very strong sounding board,” he said.

Not without hiccups

The coordination was not always smooth, and lapses did occur. Federal officials were uncomfortable with Melbourne’s extreme lockdown and felt the state border closures went too far. Hunt, Morrison and federal health advisers tried to criticize the rules without undermining overall confidence in the response.

While opinion polls show strong support for the tough measures, many people have been badly affected. Australia entered its first recession in 29 years, small businesses have closed, and reports of depression are up. On Tuesday, an anti-lockdown protest in Melbourne turned violent. Police arrested 404 people.

Melbourne lifts one of world’s longest lockdowns after 111 days

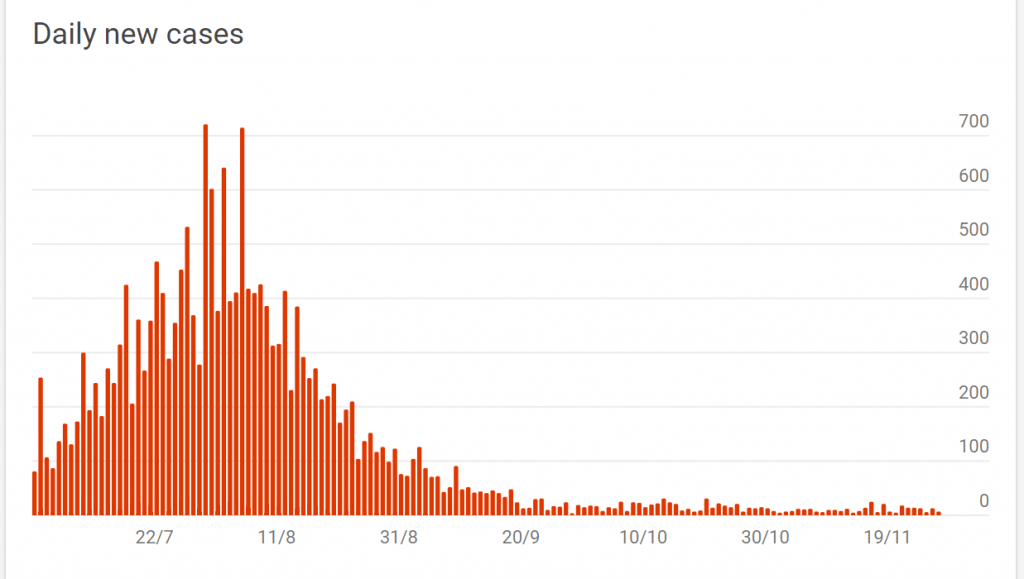

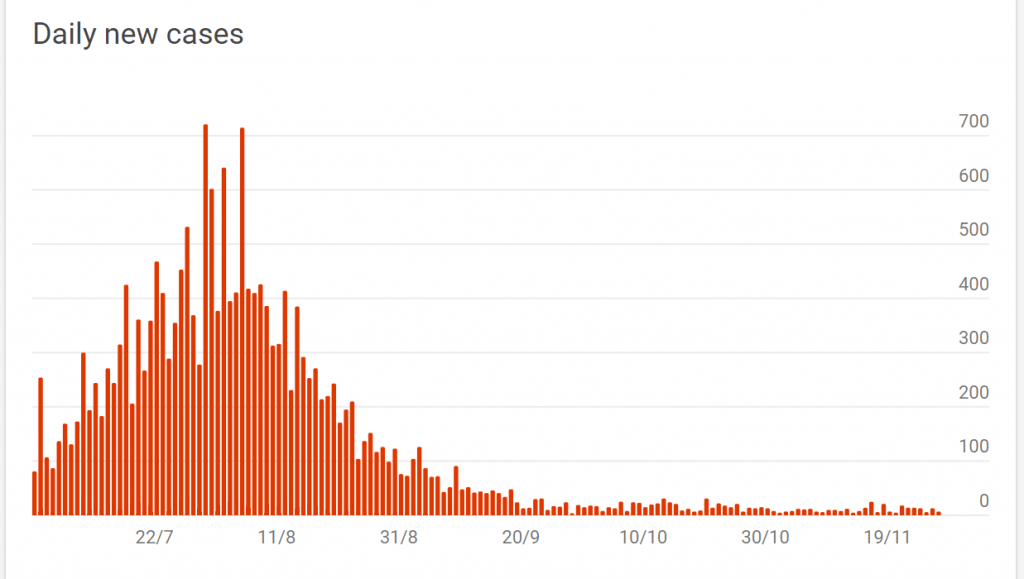

And for a time, it appeared Australia’s early success was imperiled, after lax security at hotels in Melbourne that were housing returned travelers led to a second outbreak in July. By August, more than 700 cases a day were diagnosed. It looked like Australia could lose control of the virus.

Almost all public life in Melbourne ended. After 111 days of lockdown, the number of average daily cases fell below five. On Oct. 28, state officials allowed residents to leave their homes for any reason.

Australia currently bans its citizens and residents from overseas travel, a decision that has been particularly tough on its 7.5 million immigrants.

On Oct. 16, Australia opened its border to New Zealand, which, despite limited outbreaks, never experienced a full second wave. The government is awaiting results of four vaccine trials in which it has invested.

Most Australians will have access to a vaccine by the middle of next year, Hunt said, a major step toward allowing them to travel.

The Australia day lamb add for 2020 pokes fun at the crazy state border rules:

The Australia day lamb add for 2020 pokes fun at the crazy state border rules:

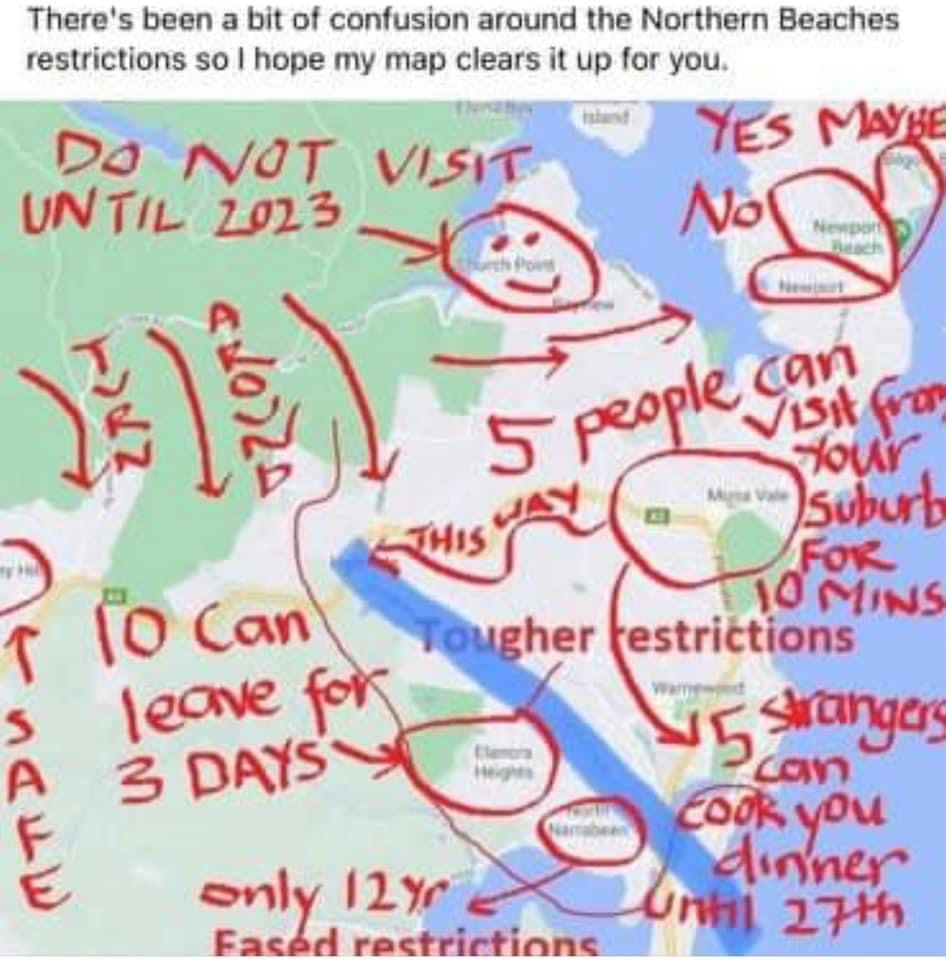

And then these:

And then these:

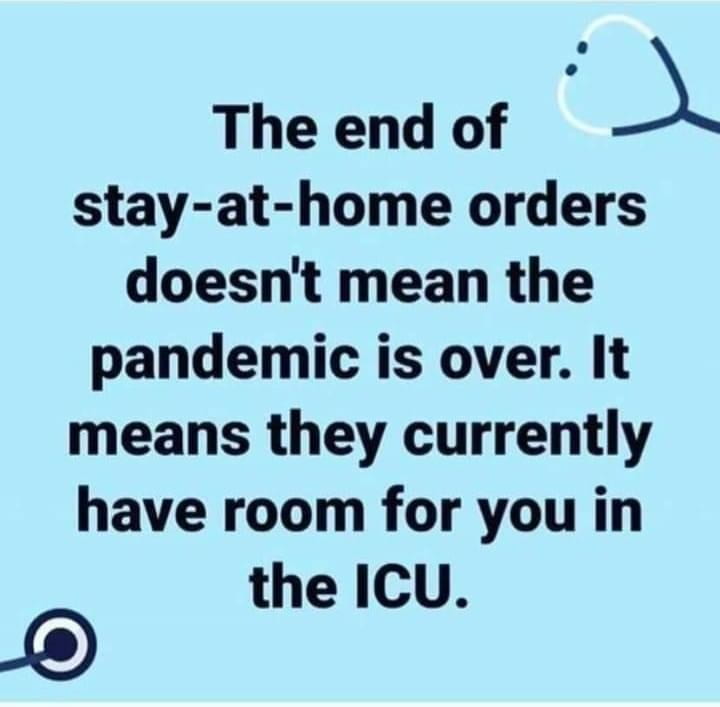

But the reality is this:

But the reality is this:

This article from the washington post is a good summary:

This article from the washington post is a good summary:

Things are still not great in Victoria. They are into Week 2 of their latest 6 week lock-down.

Things are still not great in Victoria. They are into Week 2 of their latest 6 week lock-down.

It has also been a time when ‘Karen’s have taking a beating:

It has also been a time when ‘Karen’s have taking a beating:

And the country was up in arms about this:

And the country was up in arms about this:

Most of the masks being sold are disposable. apparently after awhile your breath makes it moist and so the mask stops working, you really should be replacing it regularly. But I bet lots of people in Melbourne just put the same one on when they leave the house to avoid the $200 fine even though it is doing nothing for them.

Most of the masks being sold are disposable. apparently after awhile your breath makes it moist and so the mask stops working, you really should be replacing it regularly. But I bet lots of people in Melbourne just put the same one on when they leave the house to avoid the $200 fine even though it is doing nothing for them.

But the government, who has certainly not been shy in handing out money, is

But the government, who has certainly not been shy in handing out money, is

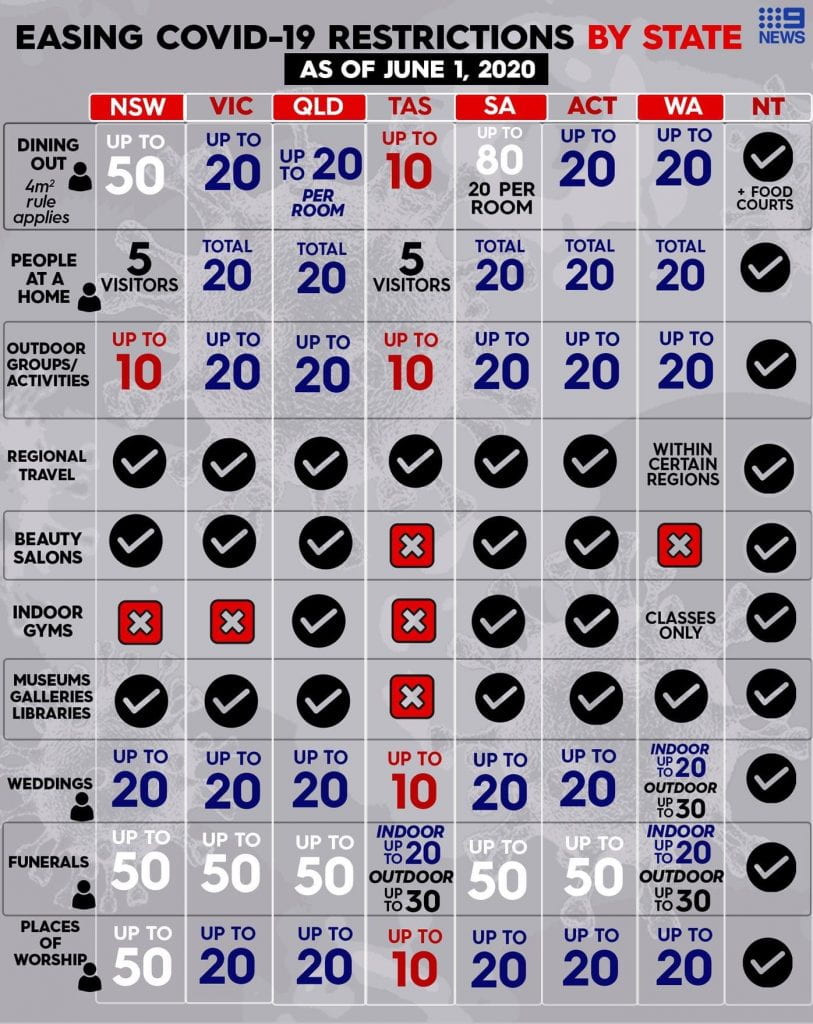

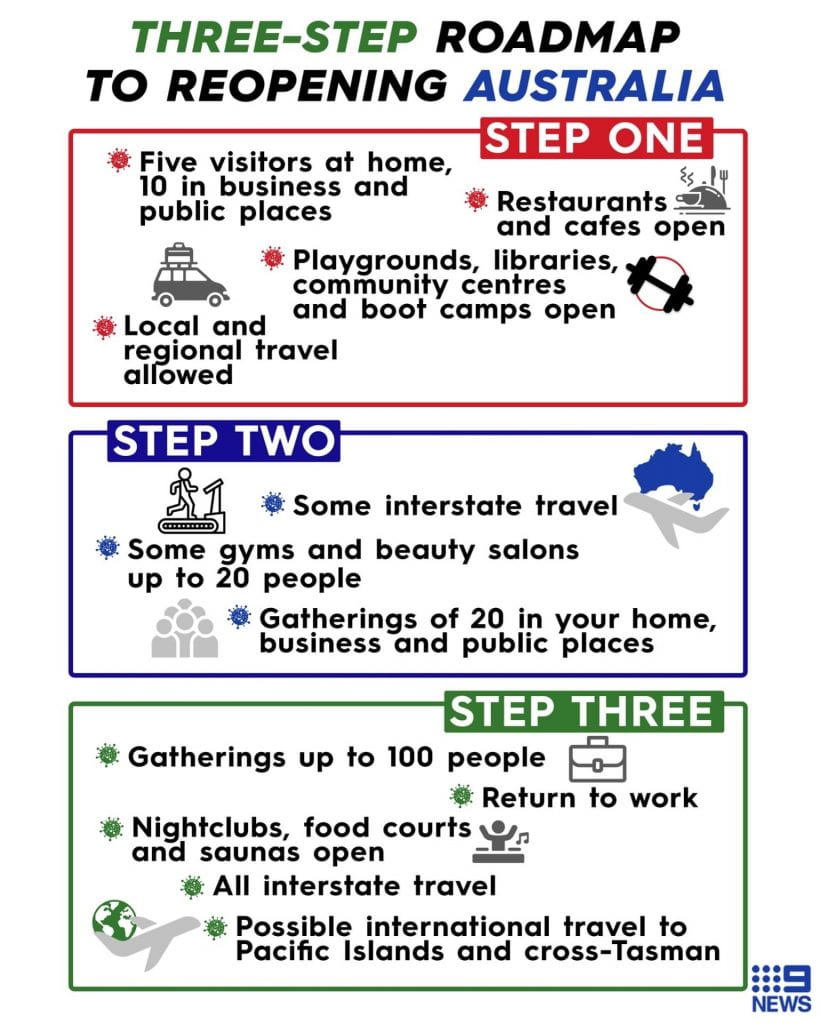

Borders are starting to open everywhere but no-one wants to let Victorians in! NSW people will be allowed in QLD for the 2nd week of the July school holidays – why the Premier didn’t let tourism have the whole 2 weeks holiday who knows. You have to fill in a declaration form and are stopped at the border to check. WA holding form and not letting anyone from ‘over east’ in.

Borders are starting to open everywhere but no-one wants to let Victorians in! NSW people will be allowed in QLD for the 2nd week of the July school holidays – why the Premier didn’t let tourism have the whole 2 weeks holiday who knows. You have to fill in a declaration form and are stopped at the border to check. WA holding form and not letting anyone from ‘over east’ in.

Interstate borders are still closed.

Interstate borders are still closed.

However we have been told to expect that cases will crop up. Within a few days of the kids going back to school Riverview had to shut down for a few day then Waverly and Moriah had a case too.

However we have been told to expect that cases will crop up. Within a few days of the kids going back to school Riverview had to shut down for a few day then Waverly and Moriah had a case too.

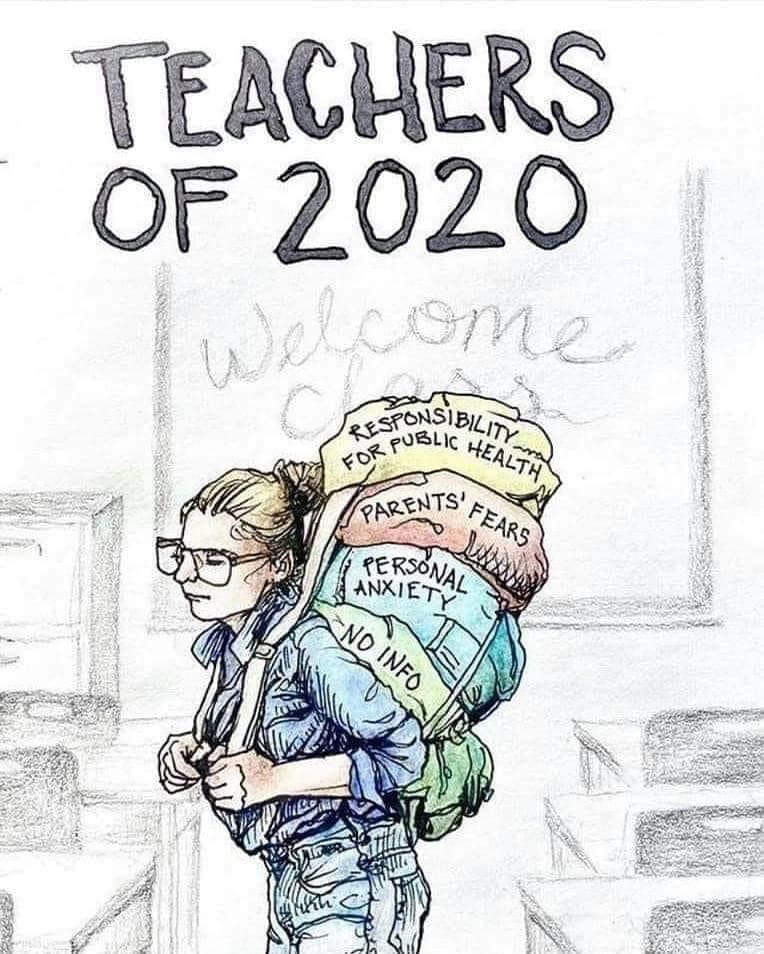

Still no work on the horizon for us though. We were the first to lose work and I think we will be the last to get back. No way anny large groups will be allowed for some time, especially in schools. We put in a brave face but it can be tough at times.

Still no work on the horizon for us though. We were the first to lose work and I think we will be the last to get back. No way anny large groups will be allowed for some time, especially in schools. We put in a brave face but it can be tough at times.

I did think this was funny though:

I did think this was funny though: